Religious institutions in Myanmar have increasingly filled the educational void, especially since the 2021 coup, by sustaining learning, community support, and leadership development amid conflict and state collapse.

Key Takeaways:

Armed conflict from the Spring Revolution, in response to the military regime, has severely weakened—if not collapsed—the formal education system, especially in war-affected areas.

University registration declined by more than 68% from 2022 to 2024 compared to the 2019-2020 academic year.

The role of religious institutions' contribution to Education has considerably changed post-2021 coup in Myanmar.

Introduction

The suspicion of teachers' involvement in protections against the military in the wake of Myanmar’s 2021 coup, and to disperse the educated youth, the State Administrative Council (SAC) targeted schools and universities. Incidents of armed conflicts, including attacks, destruction, and airstrikes on school compounds, have been widespread in many war-affected areas such as Sagaing, Chin, and Kayah (Kareni). Consequently, the closure of schools and universities is widespread. Students have been arrested, sometimes even killed. Some became members of local PDFs or EAOs. In addition to these, poverty, violence, and limited access to education have severely lessened youth aspirations for further education. After the emergence of conscription law, most university students have continuously boycotted education under military rule by leaving their countries as migrant workers or asylum seekers to resist imprisonment or recruitment. The quality and reliability of education are less guaranteed and getting worse. Hence, the formal educational system has been ruined either wholly or partially. University registration declined by more than 68% from 2022 to 2024 compared to the 2019-2020 academic year.

As formal education is inaccessible in conflict areas, religious institutions took a crucial role in filling the educational void. Not only did monastic and faith-based schooling provide indoctrination and theological education, but they also offered broader academic and leadership training. They historically served as more than places of worship, congregations, and sacred places. They have been centers of learning, community development, social inclusion, and the birth of next-generation leaders. After the 2021 coup, Christian seminaries, Buddhist universities, and Islamic madrasahs have maintained educational programs by offering religious and secular learning amid political turmoil.

Pre-colonial Religious Institutions’ Contribution to Education

Monastic education was one of the best educational systems. At 3 or 4, children, especially boys, were sent to the nearest monastery to learn basic literacy skills in Burmese and Pali, the importance of Buddha teachings, and astrology. It was targeted at the Theravada Buddhist population, especially the major Burmese people. Shah (2019) argues that it was also used to civilize non-Buddhist ethnic groups and to assimilate people into the lowland polities. Moreover, cultural standardization and social norms were transmitted from the monasteries.

As monks ran monastic schools, girls were not admitted to education. The Rights to education and gender equality were not recognized. Traditional conceptions embodied Burmese culture and living standards. Rarely did some girls from elite or royal families receive education, and even then, it was not prioritized.

Furthermore, the education itself did not intend to accommodate diverse ethnic groups within a nation, and it aimed to reinforce a respect for tradition, hierarchy, and Burmanization. A study from the University of Auckland on the Role of Education in Myanmar found that the Myanmar Education system allowed the de facto authority to control its curriculum. Unfortunately, no rulers or Burmese Kings attempted to educate minority ethnic groups, such as Mon, Shan, and Rakhine. Oral tradition was mainly used amongst ethnic people.

The Rise of Western Education/ Church-based Education in British Colonial

Similar to monastic education, church-based education also played a role in manipulating civil control, regulating social movements, and serving as de facto agents of colonial power. All kinds of Christian missionaries, including Baptists, Catholics, and Anglicans, used the Bible as an integral part of the curriculum; however, there were slight alterations to the adopted education system based on the particular religious practices, traditions, cultures, inhabitants, and geographical landscape.

Unlike the education in monasteries amongst Burmese groups, Christian missionaries endeavoured to address the essentials of education to excluded girls and marginalized groups from rural and mountainous regions, for instance, Kachin, Chin, and Karen. However, the homosexuals had not been counted yet. No matter what, Church-led education was a good initiative for ethnic minorities, which could bring the Western governance system, education, a literacy movement, a sense of community, Christian identity, and social mobility from animism. At the end of colonization, those educated in missionary schools became active leaders in their communities, insightful human resources like interpreters, teachers, nurses, and administrators, by challenging societal norms, traditional perceptions, and adapting to political changes in Myanmar.

Religious Institutions’ Contribution to Education in Post-2021 Coup

Not only for education, but religious institutions also contribute to community hubs and development, where social stability, moral, and ethical values are prioritized during the period of national unrest. Students have been nurtured with hope and resilience by promoting compassion, community services, and social justice. What is more, leadership development, youth empowerment, and vocational training are initiated to foster the role of young people in the community with the purpose of national reconstitution during and after the revolution. For example, Islamic madrasahs serve as the sole avenue for Myanmar Muslims to receive Islamic moral and ethical principles, as the national education system excludes religious instruction for all faiths except Buddhism.

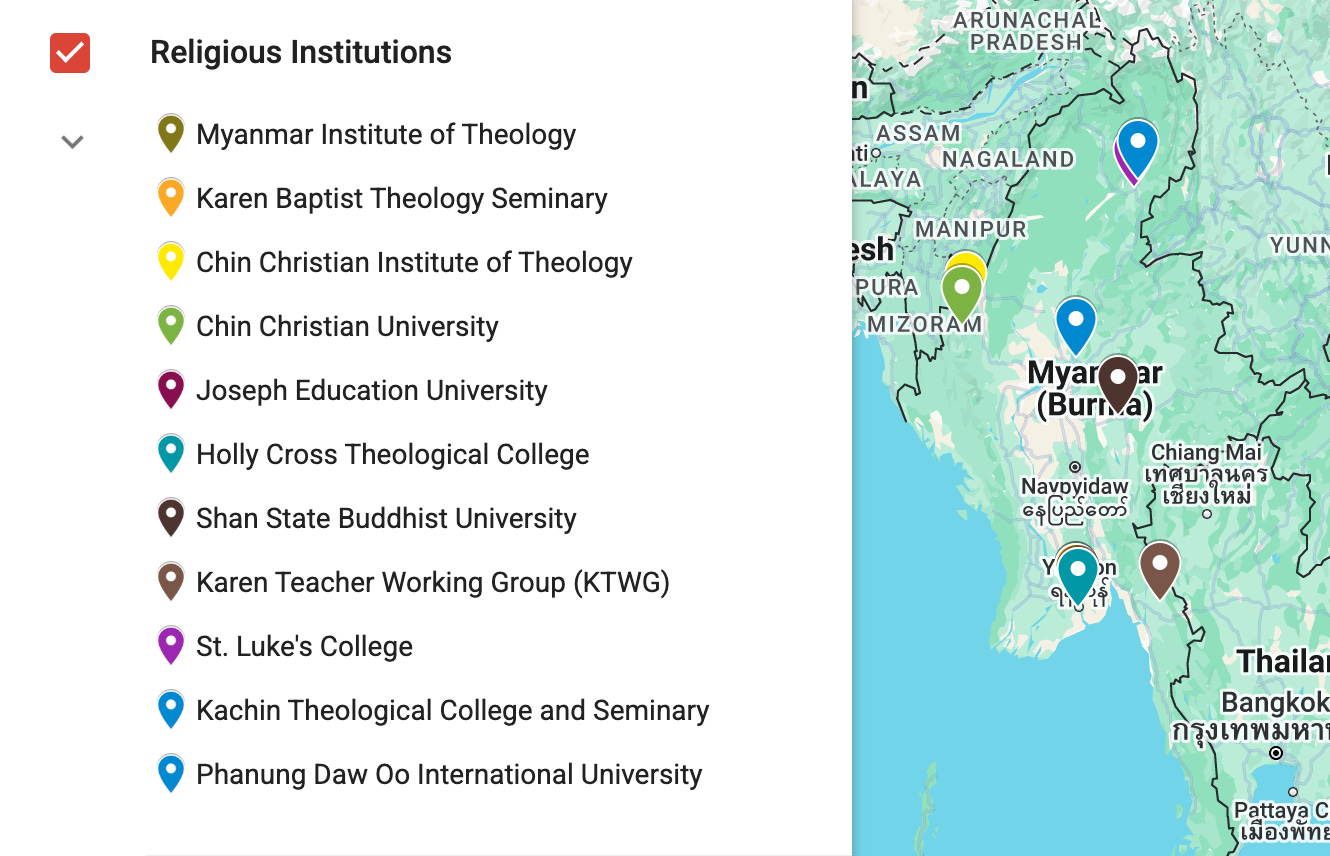

Despite the oppressive political environment, violence, and conscription law, the following religious institutions play a vital role in their respective area. Some may not be included in the map because of the limited information.

Conclusion

To sum up, religious institutions in Myanmar have played a crucial role in promoting sustainable education, not just in the wake of the 2021 coup but also throughout history. Despite the political instability, their contributions to education and community development are undeniably significant. By adapting their programs to meet broader community needs, regardless of race, religion, and geographical location, as an example of the admission requirements of the Myanmar Institute of Theology (MIT), they will become invaluable assets, particularly for those students in conflict or war-affected areas, in the nation’s struggle to preserve educational opportunities amid ongoing political unrest.

Aung Ko Ko is a second-year social studies student at the Myanmar Institute of Theology (MIT). He has experience teaching at a migrant centre and studying how political unrest affects youth aspirations in higher education.

“Advocating Sustainability, Shaping Our Future”

The opinions expressed in these articles do not represent the official stance of SRIc - Shwetaungthagathu Reform Initiative Centre. The Sabai Times is committed to publishing a range of perspectives that may not align with editorial policy.

Help Sustain The Sabai Times - Myanmar’s Voice for Sustainable Development Support The Sabai Times